Our Previous Relationships with Cooperatives via TechnoServe

During the initial phase of Technoserve’s (TNS) work with cooperatives in Ethiopia, Kaffa in Oslo imported green coffee directly (pre-CCS) and roasted a few lots from some of the TNS supported washing stations, including Yukro, Hawa Yember and Hunda Oli.

I first got involved with some of the TNS coops during the 2009/10 season. Groups of roasters from around the word were invited, particularly from USA and Scandinavia, as they were seen as discerning buyers in viable markets. TNS was presenting their work at SCAA, SCAE and at roasting community events. These presentations weren’t really within TNS’ self-proclaimed mandate nor model, rather it was done to train and empower local representatives to learn how to market themselves.

KAFFA bought some lots but service was slow, samples hard to get, lots were sold out before one had time to provide feedback, and even if one visited to cup and buy on-site, the unions seemed to favor the ‘bigger’ roasters. When ‘dealing’ with the coops, one quickly learned that they didn’t truly have control over their products. It felt like one had to scramble to get ahold of something rather than being able to pick and choose properly, the way we’d do it in, let’s say, Kenya. Commitments were certainly not honored. It was all quite discouraging.

When I re-visited at the end of the harvest in 2012, the cooperatives were not just under-funded; they’d had little to no money just before the beginning of the harvest to pay for cherries. When I additionally learned that the harvest had been very low, I initially thought the low volume had to do with little yield per tree/farm. In reality, the low volume was due to farmers not being able to afford to deliver cherries to places that couldn't pay them up-front. This in turn meant low volumes at the washing station. Coop washing stations could only purchase as much coffee cherries as their credit line allowed them to. The irony of the TNS coops’ credit drought was that Oromia Union, their partner-in-crime, didn’t lend their coops the resources needed to buy cherries and hence, thrive. Even though customers were lined up to buy, complete dysfunction ruled at the most basic levels.

The quality management of the cherries was also poor and this related to the above economic problems. When you’re struggling to pay in the first place, you end up scrambling to get what few cherries you can afford. This is not the time to be scrutinizing the cherries’ maturity and uniformity.

Just as discouraging was the administrative and fiscal dysfunction. I wanted us to stay away as long as the Oromia Union stayed involved.

Now, five years later, the time feels right on many levels. And I’d like to take this opportunity to reflect on our previous experiences, as well as provide some background info that will hopefully be helpful to you. Full disclosure: I am “collecting” this information from memory, so bear with the fact that some of it is anecdotal.

Former TechnoServe staff, Aansha Yassin

TechnoServe’s Coffee Initiative

TechnoServe (TNS) is an NGO that was founded in 1968 and has been funded by the likes of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. TNS works with development initiativesin many countries including within Africa and mostly with agro-businesses — coffee amongst others — utilizing local natural resources and human potential to create economic advantages. What I like about the Gates Foundation approach is the clearly expressed belief that making good business (product and management) is both the means and the goal. In other words, participating communities utilize what they already have – local resources and the development of community members’ own knowledge and skills – to create better economic opportunities.

In Ethiopia, the Coffee Initiative was started in 2008 with investment from the Gates Foundation. This allowed TNS to do coffee work on a large scale and in new places like Ethiopia and this particular project had a five-year mandate. One of the beautiful ideas and high ambitions of the program was to empower local people to learn about the specialty coffee field by crafting great coffee: managing it as a business; doing lot separation; assessing quality through cupping; communicating monetary value through quality; and finally, marketing and offering it to a discerning marketplace.

TNS intelligently set out to focus their efforts in the western regions of Ethiopia. This part of the country has always had a rich history in producing coffee. As far as we know, this was the birthplace of coffee. Still at the time that TNS came in, coffee from the west didn’t have fame, nor was it fetching the high prices coffees in the south were getting (such as e.g. washed Sidamo and Yirgacheffe).

The western lowlands are home to Bebeka Estate, which up until recently was the largest government owned estate farm. This estate is now owned by Mr. Al Amodi, who is also the current owner of the Horizon Dry Mill. Also located in this region, are areas such as Djimmah, which was synonymous with low grades of naturals.

Although many areas in the west do have the altitude for producing high quality coffee, the infrastructure wasn’t in place to produce and supply good coffee, whether because of the lack of equipment to produce it (very few wet mills), or getting products to the marketplace (poor roads). Thus, TNS’ strategy was to change the perception of West Ethiopian coffee by both efficiently producing washed coffeefor a specialty coffee market, and by making this coffee logistically accessibleto the market. Though roads were built and upgraded independently of TNS initiatives, these kinds of efforts went hand-in-hand.

The TechnoServe Way

TNS proposed that the coops install eco-pulpers at all the washing station projects they got involved with. This was a controversial prospect at the time, given the strong tradition up until then of the Ethiopian wet process being about fermenting with mucilage before washing. As we know, eco-pulpers have benefits, including saving water and requiring a lower up-front investment than the traditional wet process set-up with its many large fermentation tanks and washing channels.

Part of the TNS agenda was to help build equitable business projects, even helping with the financing, implementation of transparent bookkeeping, and overall good management by:

- Facilitating the process of applying for and getting loans to buildthe technical infrastructure: buying eco-pulpers, building washing stations and drying beds;

- Facilitating the process of applying for credit from banks so the coop could buy cherries. When a farmer arrives with coffee cherries, on any given day, the coop is expected to pay for the delivery on the spot. Thus, a lot of cash is required even before the start-up of the harvest season. Not to mention all the cash required to carry out the season;

- Helping to create a marketing plan (on behalf of the union): market outreach, market access, quality control and sample distribution

- Operational management, planning, and fiscal control.

Some of the most successful TNS coops managed to pay back the investment of equipment and infrastructure in less than 2 years, which is considered a great success by any business standard.

The ECX

TechnoServe During the time of the Revamping ECX

Little did TNS know that their program would be in stark contrast to ECX’s coming implementation of anonymity in the auction process. The new ECX structure was coincidentally put in place very soon after the TNS cooperatives were inaugurated and ready to hit the market with their attractively traceable coffees. The Coffee Initiative's original intention in Ethiopia was never to work with the Unions. In the first year, 2009, it tried to create a model where coops could work directly with private exporters. However, the Unions/government brought this process to a grinding stop. Eventually, all the coffees had to be taken over and exported by the Unions, and the contracts renegotiated. This was a major blow to the program because no one, including TNS, trusted that the Unions would be efficient, transparent, etc.

Specialty coffee buyers were flocking to TNS’ washing station projects. Although the coffee quality was not top-notch in the very beginning, the model at least provided a transparent trade model and TNS was pushing to make sure the farmers and their communities were rewarded with premium prices above the Fair Trade/Organic models.

When a washing station is owned by a cooperative, the contributing farmers collectively own the coop, but they must nominate a union to handle their milling and marketing for which the coop is charged a service fee. It usually makes sense to get these services from a union that is involved in the region, and hopefully it is also offering competitive terms. Even if the milling fee is regulated by law, unions have a reputation for taking advantage of the coops by charging the maximum fee possible and/or screening and processing lots to their own benefit (e.g. ‘mixing up’ lots, blending and even stealing).

The coop-union relationship is generally one where the union arguably has the ‘upper hand’. Since the union ends up with the parchment coffee in their possession, and being that they become the party that markets the coffee, they are the ones to send samples out to potential buyers.

In other words, even if a union is intended to be an intermediary part in the transparent relationship between a producer and a buyer, the unionis the primary contact and by default becomes the ‘owner’ of the relationship.

All this said, that dynamic briefly changed as soon as the TNS coops and washing stations earned their own fame, consequently bypassing the unions in building relationships directly with their end buyers (roasters).

TNS coops were obliged to deliver to various unions, as made geographic sense. Unfortunately, this only lasted for the first year of operation under TNS supervision. Once the Oromia Unionand its powerful and charismatic leader saw the success and prestige associated with trading directly with affluent coffee buyers around the world, it didn’t take long before all the TNS coops were forced to mill and market their coffee through the Oromia Union.

Oromia Union’s experiencewith lot separation, handling of the respective samples, and the necessary marketing efforts were generally not well developed initially. To overcome this, TNS opened regional offices with cupping facilities, training local staff and offering opportunities for buyers to access coffee without having to depend on the union. These efforts were meant only to be an temporary solution, while Oromia Union was supposed to equip itself with skilled staff, adequate systems and protocols, and building marketing strategies.

In my opinion this became and remained the weakest link with the TNS-developed supply chain. When TNS ended their project term, Oromia was still struggling to get things right.

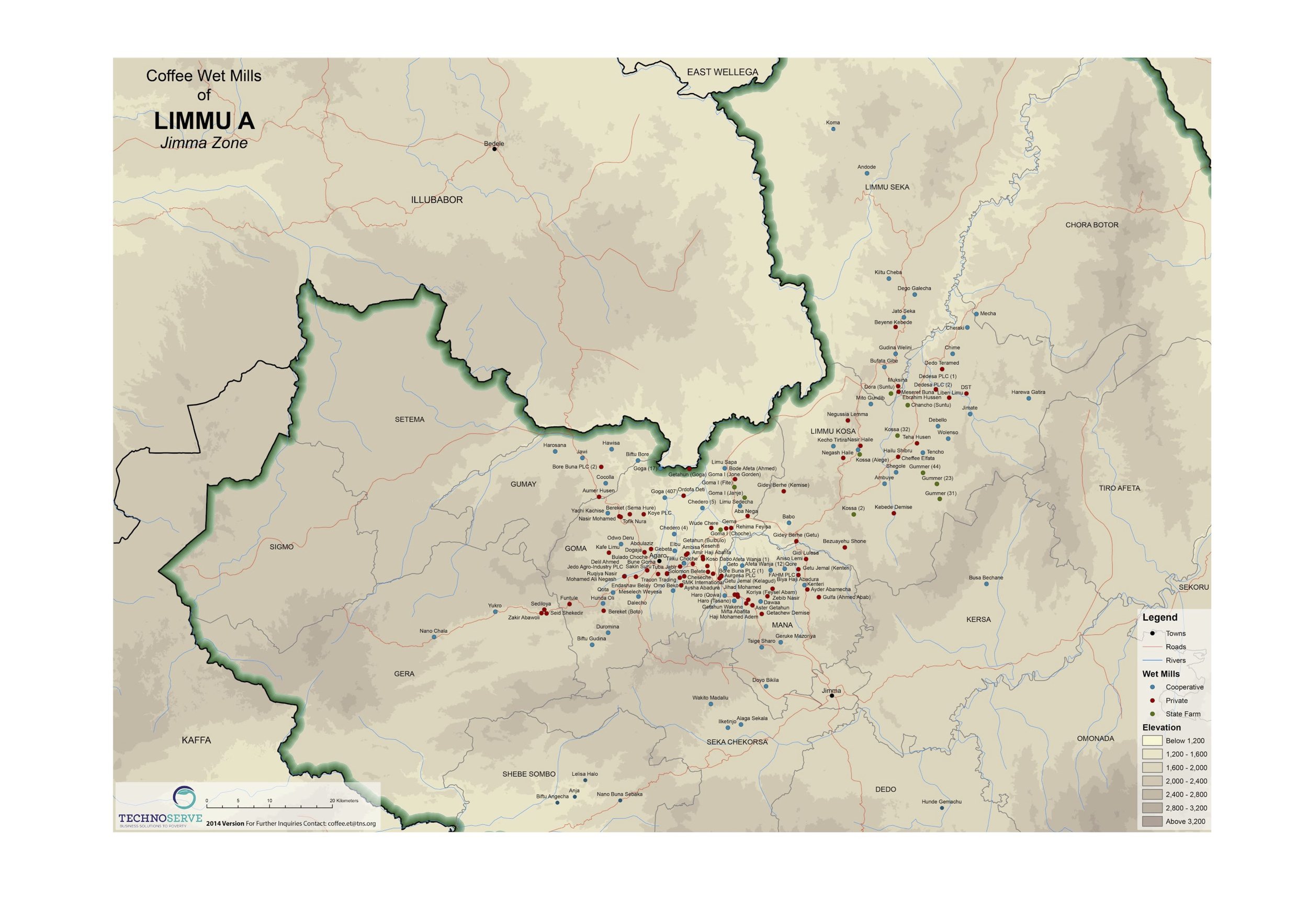

Limmu is primarily where our coop coffees this year will come from

Returning to Cooperative Coffee

I am very pleased to announce that CCS is going into this season with a more diverse approach to sourcing and buying in Ethiopia. In addition to offering stellar ECX coffees; and micro-lots from private estates; CCS will introduce cooperative coffees to the menu. It is promising indeed thus we are looking forward to presenting a carefully curated list of lots from thoughtfully selected coops in the Limu/Djimmah region of the west!

The reasons for this optimism are these necessary turn of events: 1) Other Unions, for all the above-mentioned reasons, have emerged to service the coops; and 2) Quality, compliance, and commitment seem to hold a higher priority than in the earlier years of my experiences with the cooperatives and the Oromia Union.

We cannot wait offer you to taste the 'fruits' coming from all these emergent changes. Enjoy!

Robert

—founder of KAFFA and Collaborative Coffee Source (CCS)

Corrections: 1) the previous version incorrectly stated that TechnoServe was founded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and has been corrected to reflect the fact that the NGO was founded in 1968 and that the Gates Foundation is one (albeit a large one) source of funding for TNS.

2) it was never TNS' original intent to work with Unions, as was implied in the earlier version. The post has been corrected to reflect the fact that TNS' aim was to work directly with cooperatives, independently of the Unions/government from the beginning.

Cupping back in 2012