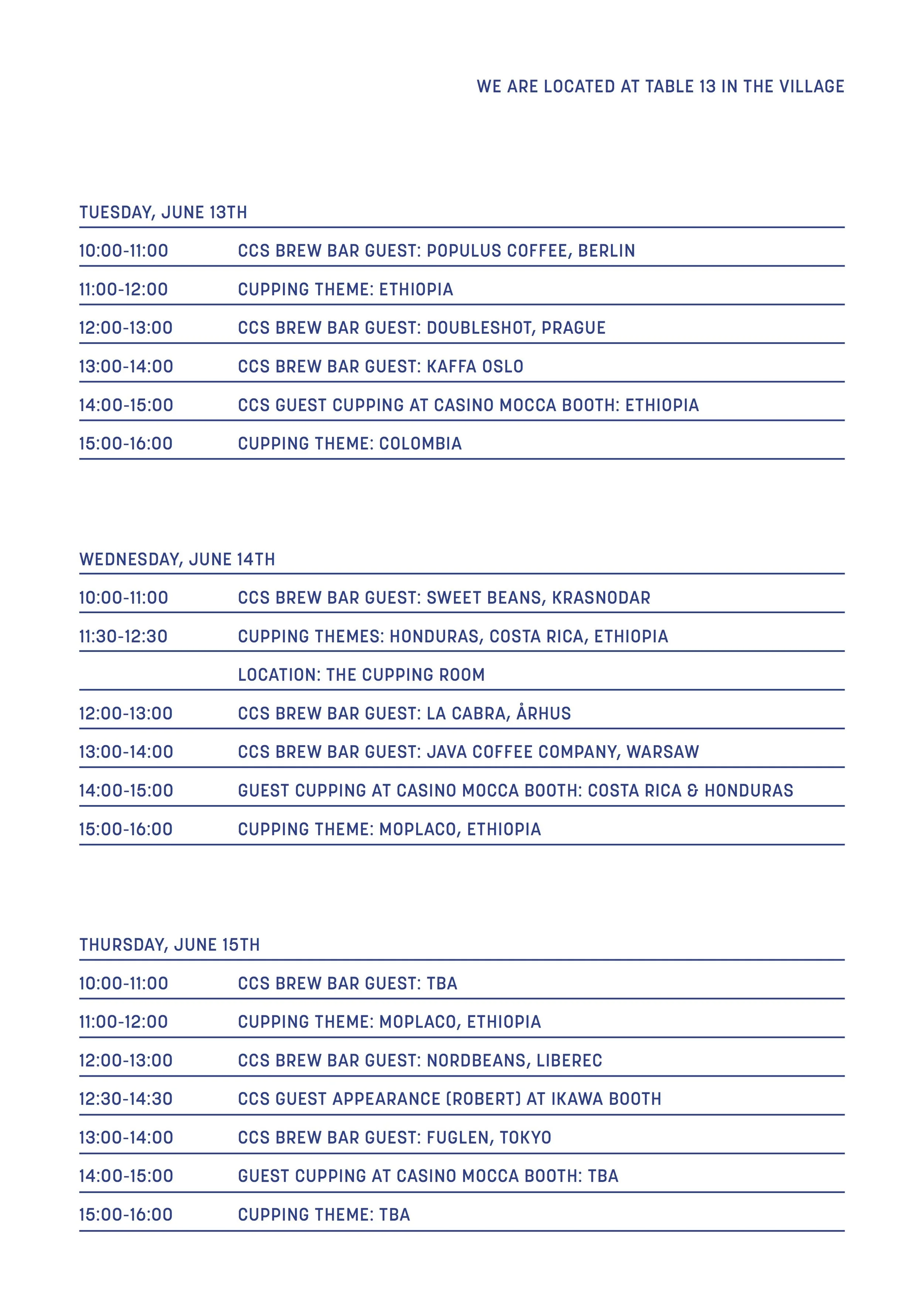

Photo taken on a Hasselblad by Tuuka Koski

Dear Daniel,

We just learned that you will not be there when we go to visit next time, that makes us very sad. I was looking forward to seeing you again, hugging you again, seeing your beautiful wife and children and grandchildren again. They will all be there, I know that, but you have been the anchor Daniel, you have been The Father Moreno, and The Farmer of ‘El Campo’. We will miss you.

We would, as always, meet at your house upon the hill, and it would have been a heartfelt revisit. We’d try to hold back some tears, but none of us could really help it. It has been like that for many years now, and that’s why. This is business for both of us, but we also know that we depend on each other, and over time affection and care and a sense of responsibility builds. It is as inevitable and natural as in all other aspects of life, certainly when meeting such a graceful man like yourself.

As the routine has always been, you would be eager to show us the coffee on the drying beds just behind the house, behind the fermentation tanks, and every time there would be something new that had been done since last time we met that we’d look at and discuss. I am sure everyone that has come to visit has the same image as I have of you, standing by the drying beds, humble yet proud, while quietly and gently raking the coffee with your hands, always picking, always moving, always improving.

Seemingly, all of your nine children have inherited this from you, of working hard and always moving forward. You have raised a large family, I will admit that we sometimes joke about going to Moreno Town when we visit because the whole place up in El Cedral is crowded with people, all ages, carrying your last name. The first Moreno I met was Miguel, your oldest son. He has responsibly taken the role, as the first born son sometimes has to, of carrying the baton, maintaining the legacy that you have left them with. Yet there is a family behind him, a whole community of people ready to work on that now, all thanks to you. Well, as we both know that is something that Miguel and yourself have had serious discussions about since before the ‘new era’, back in 2004, when you were about to give up coffee farming altogether, the work was too much of a struggle, not well paid by any measure, and many of your children were trying to make a living by working abroad. But Miguel convinced you to give it one more chance, he was back in Santa Barbara for a short while, from his work ’en el Norte’, and you let him prepare a lot from El Filo and submit a sample to the first Cup of Excellence that year. He succeeded with that one, you had a winning lot yourself in the CoE from El Campo the following year and everything since then is history.

Dear Daniel, rest in peace my friend. You are not going to be around us in the same way anymore and we will miss you oh so dearly, but don’t you worry. We will continue to take care of each other, by working hard and working together and looking after each other. You have planted that in us, and planted many seedlings in the soil, and nourished them to become beautiful trees that you have taken so well care of throughout a long lifetime. We’ll continue to enjoy the fruit of your labor, a labor of love. El Padrino del los cafes delociosos de Santa Barbara, mil Gracias!

With Love,

Robert

& Bjørnar

& Collaborative Coffee Source’s team and family and friends

& Kaffa and Kaffabutikk’s team and family and friends

& Java and Mocca Coffee shops’ baristas and family and friends

& our customers, Kaffa, Robert Kao, Sørlandets Kaffebrenneri, Nordbeans, Cemo, Åre, Da Matteo, Audun, Sey, 4letter word, Reveille, and Common Room Roasters, all loyal to your coffee year after year

& coffee lovers all over the world.

Related posts